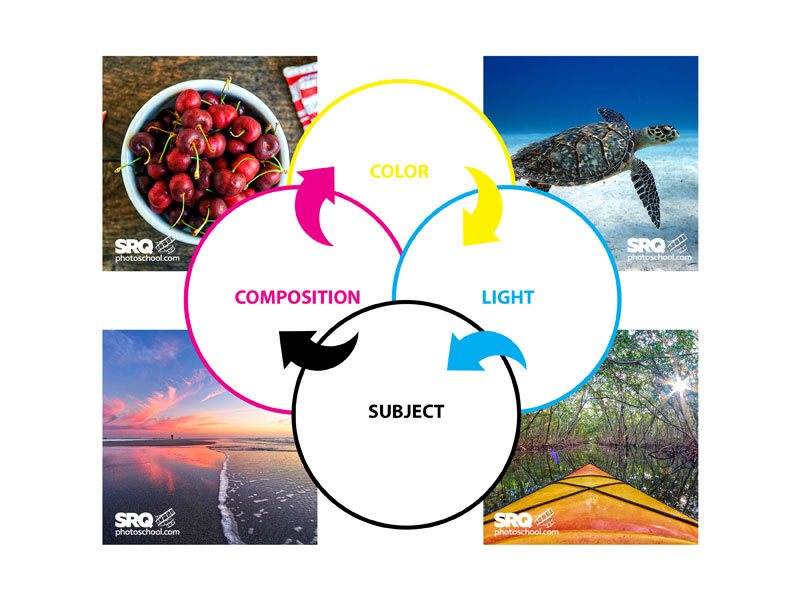

Anybody who has taken one of my workshops will remember that Light is one of my 4 key elements that are paramount to a great image (along with color, composition and subject).

We talk about quality of light a lot in photography. I often use the word magic a lot when it comes to light, and tell students that great photos require magic light. But what is magic light?

To answer that we need to understand that light varies greatly and has lots of different qualities, depending on factors like the the source, time of day, season, location and so on. Light can be extremely hard (one extreme) or very soft (the other extreme) or anywhere in-between. It takes time to appreciate the nuances and variations of light and learn how to use light that suits both the subject matter, and the style that you are shooting. Chances are you’ll never get the absolute perfect light to match you subject as it changes by the second and is influenced by many things out of your control but the better you understand light the higher your chances are to harness its power and improve your chances for a magic image.

What is hard light?

Hard light is a strong, directional light that casts deep, hard-edged shadows. You typically get in the middle of a sunny, cloudless day, or from an unmodified flash head.

Hard light, in general, is considered bad lighting for many types of photography including portraits as it tends to be unflattering as it enhances detail showing many imperfections in skin and texture. But remember, the light needs to match the mood you are trying to invoke so not all hard light is necessarily bad.

I repeat, hard lighting is not necessarily bad. I love to shoot athletes and sport subjects in hard light. Many objects lend themselves to hard light as well as it accentuates detail.

Often hard light lends itself very well to black and white photography.

Hard light is considered unsuitable for portraits because the hard shadows create too much contrast across the model’s face and are not flattering. However, you may be able to work in hard light with a male model, especially in black and white, as it tends to suit the ruggedness of a man’s face. Regardless of whether your model is male or female, simply facing them into the light so that shadows are as small as possible can work well.

What is soft light?

Soft light is that which casts either no shadows, or shadows with soft edges. It is more suitable than hard light for many subjects, including many types of landscape and portraits (but especially portraits).

For example, if you are taking someone’s portrait during the middle of a sunny day, then one of the best things you can do is find some shade, and take a photo of your model there. The softness of the light, and the fill from the brighter, sunlit surroundings, is a very flattering type of light that makes the model’s face glow and creates large catchlights in her eye.

Environmental portraits are great in natural soft light. if you feel the image is too flat you can use a bit of fill flash to give them a bit more pop or contrast.

You also get nice light for portraits after the sun has set at the end of a sunny day, when the sky is filled with a soft glow from the last rays of the setting sun. This works best during the longer days (and twilights) of spring and summer.

If you are using flash, then a modifier such as a softbox or umbrella softens the light, making it more flattering for portraits

In-between light

I’ve just described several scenarios, starting with midday sun, which is very hard, through to shade or twilight, where the light is very soft. The truth is that most light falls somewhere between these two extremes.

In this image I used indirect natural light from a large window to provide defused illumination of the subject in a relatively dark room and filled in the shadows slightly with a fill flash bounced off a high ceiling as to not over power the natural soft light. Using this type of balanced lighting indoors also help balance the background and provide a more natural look rather than using flash alone.

For example, lets say you are taking a landscape photo on a sunny day. The light changes as the sun gets lower, softening and changing in color. The exact changes depend on the time of year, atmospheric conditions and the weather but suffice it to say images shot in the early morning and late evening have a much broader color range.

The key is to find the point at which the light suits your subject, in the style that you’re trying to shoot. Depending on what you want to achieve, the light is most likely to be suitable sometime during the transition from the hard light of the day to the soft light of twilight. It’s up to you to familiarize yourself with the lighting conditions in the places that you shoot, and to learn to recognize how hard or soft the light is, and when the quality of the light matches the subject you want to shoot.

Size of the light source

I think the best way to evaluate the quality of light is to learn to look at it and assess the direction it’s coming from, plus the hardness or softness of the light, for yourself by seeing how it falls on the subject. The key factor that differentiates a hard light source from a soft one is the size of the light source relative to the subject.

This Westcott Softbox in relation to the subject is large, producing a soft natural looking light. A favorite of studio professionals. You can achieve similar effects with indirect light from a window or under an awning on a bright day.

For example, if you use a flash head without a modifier to take a portrait, the light is hard because the light source is much smaller than your model. To make the light softer, you need to use the largest modifier you can and move the flash as close to your subject as you can.

The light on a sunny day is hard because the sun is small in relation to your subject. If you were able to look at it without damaging your eyes it would appear to be just a dot in the sky.

Yet if it is cloudy, foggy, or raining, the weather conditions diffuse the light, spreading it out so that it seems to be coming from the entire sky, rather than a single point in the sky. The light source is now very large compared to the subject, and the light much softer.

A similar diffusion effect occurs as the sun nears the horizon at sunset which is why it is often the preferred time of the day to shoot.

Your turn

Hopefully this discussion has helped you look at light in a different way. There really is no “BAD LIGHT” and by understanding it better your images will be a little more predictable or you can use the right tools to work with the light you have in lieu of battling it as many of us do. Diffusers, fill flash, moving into shadow areas, closing blinds are all simple ways to work with existing light or benefit from the light you have. Now it’s your turn to experiment and with a little practice your chances of getting that magic light will improve greatly.