A simple way of looking at image size (resolution)

I’m constantly reminded each week by students that many don’t understand image size and image resolution and what they mean. I often request an image or art for a print application and receive a postage size piece of artwork that is supposed to represent the artwork used in a full page ad. Honestly, I’ve been really remiss for not discussing this long ago. I wish there were a more simple way to discuss it in only a few sentences but unfortunately, to have a good understanding it will take a little longer than that.

When it comes to understanding digital image resolution and how it pertains to image size, ultimately all that matters is the number of pixels contained in the file. It’s not about DPI (dots per inch) or PPI (pixels per inch) or how many inches the “Info Key” (command + i) says your photo is. What matters is the area resolution of the file, measured in pixels. When you talk about the resolution of an image file, what they’re really talking about is area resolution because area resolution dictates how large the file really is.

A really good way to look at this is from William Sawalich as published by Digital Photo Magazine: Let’s compare the size of an image file to the size of, say, your patio as an example. If you have a patio paved with bricks, its size is determined by how many bricks you have, right? (Or, put another way, you need more bricks to make a bigger patio.) And if you want to measure that patio, one way would be to just count the bricks. A patio that is 20 bricks wide and 30 bricks long is comprised of 600 bricks total (20×30). That is, in fact, the area resolution of the patio: 600 bricks. It will always be larger than a patio comprised of 300 bricks, and smaller than a patio containing 1,000 bricks. Simple.

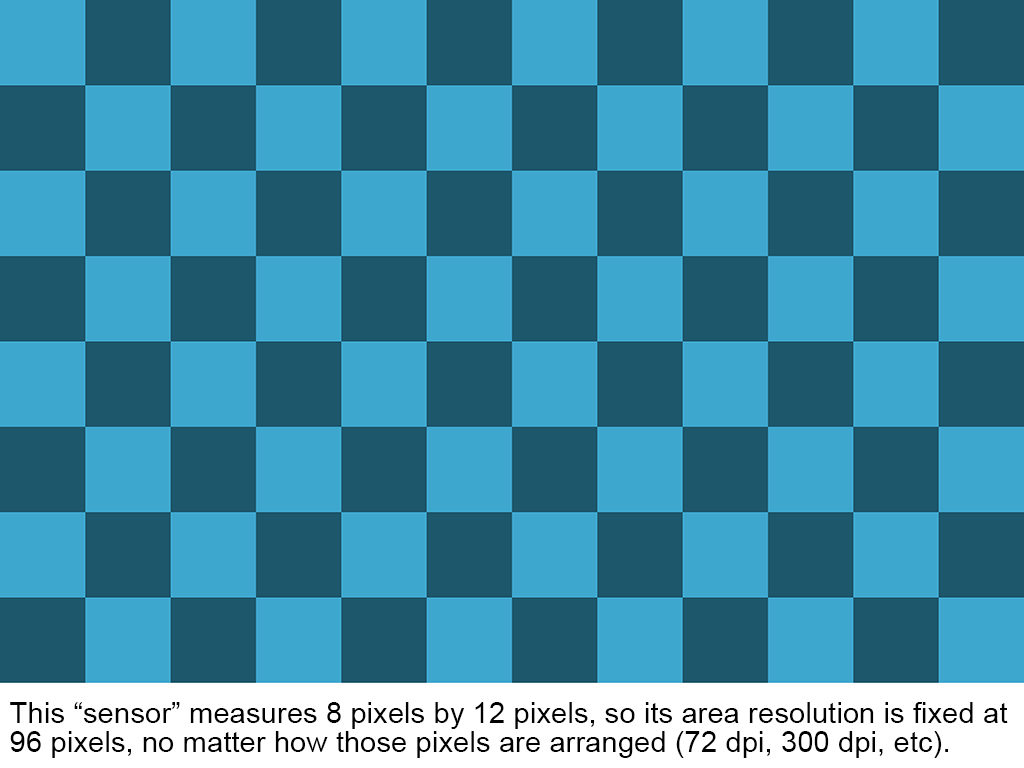

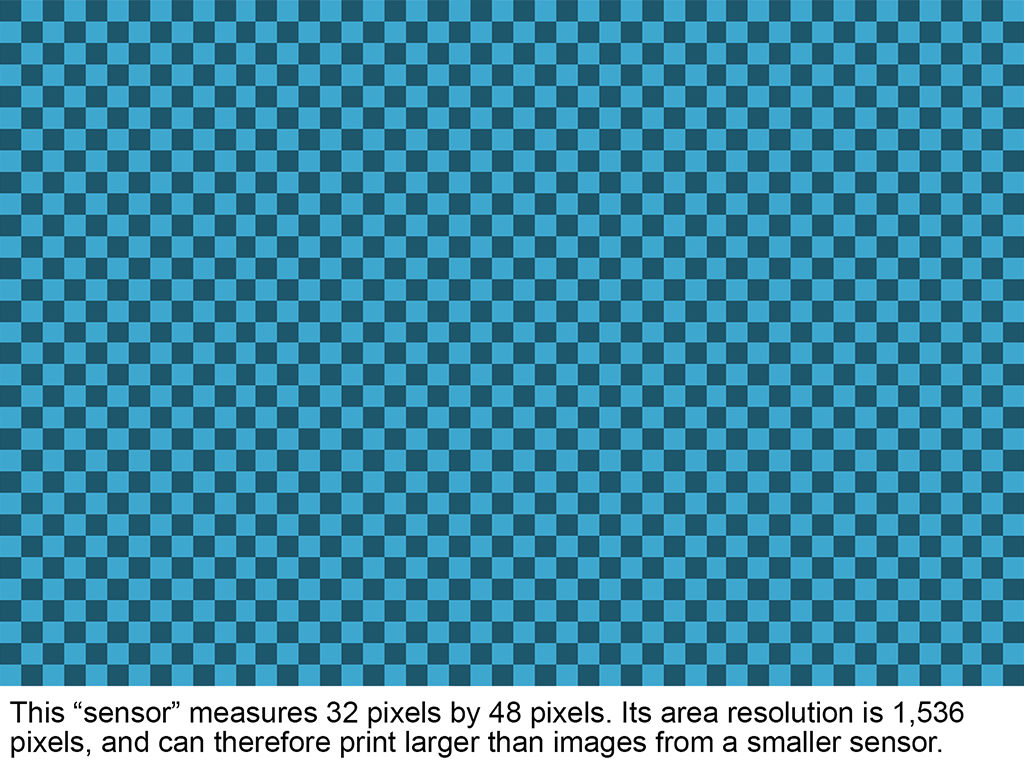

Switch those bricks to pixels, and now you’re beginning to see how the number of pixels in an image file—or available on a DSLR sensor—directly determines how big the image size will be. An image file that is 2,000 pixels on one side and 3,000 pixels on the other has an area resolution of 6,000,000 pixels. That’s a much smaller file than one with, say, 20,000,000 pixels—which is what you get if you have a file 4,000 pixels on one side and 5,000 pixels on the other. Expressed in another way, a million pixels can be referred to as megapixels; so a 20-million-pixel area resolution is, in fact, 20 megapixels.

So, going back to the patio analogy, you can see how a patio comprised of 20-million bricks would be a lot larger than one made of just 6,000,000 bricks. It gets more tricky with pixels, unlike bricks, as pixels can be packed tighter in a given space to make an image look clearer and more detailed. This is where dots per inch (DPI) comes in. DPI is often used to refer to sensors and image files when really pixels per inch (PPI) would be more accurate. In any case, it’s a measure of how many pixels are crammed into an inch. The more pixels in an inch, the more detail—but also, the smaller the print.

Think about it: It all starts with a fixed number of pixels (the area resolution) that your sensor has provided. If you take that fixed number of pixels and squeeze them 300 at a time into an inch, that’s a lot of fine detail in that inch. But if you put, say, just 100 pixels into an inch, you’re losing some of that fidelity—though now those pixels would stretch three times farther. If the long dimension of an image file is 3,000 pixels, at 300 dpi your image will measure 10 inches in length. At just 100 dpi it will measure 30 inches in length; a lot bigger, yes, but with less detail than at 300 dpi.

Interestingly, you can compare the difference between an 8×10 print and a huge billboard for more clarity on the concept. The 8×10 print likely has lots of pixels per inch—like 300 dpi—to look good at an up-close viewing distance. But a billboard is much bigger and viewed from much farther away, so it doesn’t need to have nearly the same DPI to look good. It might look just fine from 100 feet with those pixels divided up at 75 or even 50 dpi. The latter DPI would create a print at a whopping 60 inches long out of the same file that at 300 dpi could only reproduce at 8×10 inches.

The point of all this is to stop thinking about DPI as indicators of the actual size of an image file. It is, in fact, the number of pixels in the file—the area resolution—that determines the size of the file. More pixels equates to a bigger file, regardless of how many of those pixels are packed into an inch.